Reclaiming the stories of Jane, Priscilla, and Martha: the partners of the 2nd Earl of Kilmorey – by Daisy Pullman

The 19th century Kilmorey Mausoleum in St Margaret’s holds the remains of Francis ‘Black Jack’ Needham, 2nd Earl of Kilmorey, and his mistress Priscilla Anne Hoste. The Earl’s life, and particularly his scandalous love affairs, have received a great deal of attention from biographers. The narrative of most historical inquiries has, however, focused on the character of Francis. The women in his life are largely relegated to two-dimensional footnotes in the stories of his epic escapades. This article seeks to redress this imbalance by exploring their stories on International Women’s Day 2022. We will be focusing on the romantic partners of the Earl: his first wife Jane, his mistress Priscilla with whom he lays in Kilmorey Mausoleum, and his second wife Martha.

Contemporary newspaper reports and family records have been the primary sources for this research. We do not have, frustratingly, these women’s own accounts of their lives. No diaries or autobiographies exist. We don’t have any images of Martha, and a potential portrait of Priscilla cannot be confirmed. Instead we must try to piece together scraps of information: birth records, marriage certificates, census entries, obituaries etc. to uncover their lives.

Jane Gun-Cunninghame, 1st wife of the Earl, 1791-1867

Jane Gun-Cuninghame was born into a distinguished family in Ireland in 1791. Jane appears to have had a happy, privileged childhood. She had seven siblings, including four older sisters, and the five Gun-Cuninghame daughters were renowned for their beauty and grace. Jane and Francis wed in 1814 when she was 23 and he 27, and the ceremony was held at her family home, the grand Mount Kennedy House in County Wicklow.[1] By 1819 they had 4 children together: Francis Jack, Selina, Robert, and Francis Henry.

In 1822 Francis (the senior) was granted the title of Viscount of Newry and the couple become increasingly active in high society. Newspaper reports show the new Viscount and Viscountess regularly attending balls and charitable functions in Ireland and England, and they appear to have been particularly embedded in the aristocratic circles of Belfast. One report in the Belfast News-Letter describes an 1828 ball the couple attended. Fuelled by an “abundance of excellent champagne” revellers kept the “quadrilles and waltzes” going until 5 o’clock the following morning![2]

In 1832, upon the death of his father, Francis became the 2nd Earl of Kilmorey making Jane the Countess Kilmorey. It was also around this time that the couple began living increasingly separate lives. Jane appears alone at many functions, and the ‘Fashionable Departures’ column in the papers (gossip columns recording the comings and goings of the elites) rarely show the couple traveling together.

Papers from the Kilmorey collection, held by the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland, shed some light on why this was. In 1835, in a move that seems strikingly modern, the couple had officially separated. Due to “unhappy differences” between Jane and Francis a deed was drawn up to separate their finances and divide their property.[3] The agreement also dealt with the doctrine of coverture: a husband’s legal right to control, and essentially own, his wife, a principle which permeated English common law at the time.

“The deed asserted the right of the Countess of Kilmorey to ‘live separate and apart’ from her husband ‘in such place or places and with such persons as she shall think proper as freely to all intents and purposes as if she were sole and unmarried’. The Earl of Kilmorey agreed not to seek restitution of his conjugal rights by forcing her to co-habit with him, and she was ‘freed and discharged from the restraint molestation authority and government’ of her husband. Furthermore, her husband agreed not to sue or prosecute anyone ‘harbouring protecting or assisting’ the Countess and not to ‘molest interrupt or disturb her in her place or mode of living’.” Deborah G. Wilson- Women, marriage and property in wealthy landed families in Ireland, 1750-1850, pp. 135-136

It was a divorce in all but name. The two remained married and Jane kept her title, but they went on to live separate lives. Whilst the practice was not unheard of at the time, particularly amongst nobility, it runs counter to many of our assumptions about marriage and female autonomy in Victorian Britain. Learning of their separation also helps explain some of the more puzzling aspects of this story, such as how Francis was able to live with Priscilla and raise their son without protestation from his wife at the time.

Jane remained very active in aristocratic society as an independent woman; in 1836 she presented her daughter Selina to the Queen at a ‘drawing room’ event at the palace, and she was a patron of many charitable ventures.[4] During the Irish famine of the 1840s Jane donated generously to relief efforts in her homeland.[5] Jane was very close to her only daughter; from what we can learn from the ‘fashionable departures’ columns the two were rarely apart even well into Selina’s adulthood.[6] Selina stayed close to her mother up until Jane’s death, and didn’t marry until 1874 when she was in her 50s.

Jane died at the age of 76 at Lansdowne Lodge, Putney in 1867. She left behind 3 children (her and Francis’ eldest son had sadly died young in 1852) and 12 grandchildren. [7]

Priscilla Anne Hoste, the Earl’s young lover?

Priscilla Anne Hoste was born in 1823 at Hamble House, Hampshire into one of the most powerful and esteemed families in England.[8] Her mother, Lady Harriet, was descended from the Walpole and Churchill families and sister to the 3rd Lord of Orford. Her father, Sir William Hoste, was born into relatively humble beginnings but made a name for himself as a naval Captain. He was a protégé and close friend of Admiral Lord Nelson, and a hero of the Napoleonic wars. William died of tuberculosis when Priscilla was just 5 years old, leaving her and her five siblings in the care of their mother, and appointing a former comrade Captain Waldegrave as their legal guardian.[9]

Priscilla’s childhood was spent amongst the most elite of British society. Her mother Lady Harriet was a regular guest of the royal family, often visiting privately with the queen and attending ‘drawing rooms’ (audiences with the royals) throughout the 1830s. From an early age Priscilla was accompanying her mother to parties and royal functions. In 1834, for example, an 11 year old Priscilla and her siblings attended the “Queen’s Ball” at St James’ Palace, a special event for “the juvenile branches of the nobility and gentry” also attended by a fifteen year old Princess Victoria.[10] From the princess’s journal entry on that day it seems to have been an enjoyable evening. On this occasion, at least, Victoria was “very much amused”.

“At a ¼ to 8 we went … to St. James’s for the annual Juvenile Ball…. I danced once more after supper with Lord Emlyn. We staid till 1. We came home at a ¼ past 1. I was very much amused.” Queen Victoria’s Journal, Friday 30th May 1834.

Priscilla’s life intersected with Francis, Earl of Kilmorey’s in Geneva in 1843. This meeting set in motion a complex and scandalous series of events that would tarnish not only the reputation of the Earl, but also, and perhaps more severely, that of Priscilla’s mother Lady Harriet Hoste. This narrative has been taken from contemporary newspaper reports.

It seems that Priscilla, aged 20, and the Earl, aged 60, began an affair whilst in Geneva, resulting in Priscilla’s pregnancy. The two ran away together in the summer of 1844, but Lady Harriet followed in attempt to stop them. As Priscilla had not yet reached majority (though she was just weeks away from her 21st birthday at this point) her mother was able to petition the courts in Paris to reinstate custody of her daughter.[11] A now heavily pregnant Priscilla was placed in the care of a Dr Pinel, who had been nominated by Priscilla’s guardian Captain Waldegrave, whilst the case unfolded.

The case in Paris did not go in Lady Harriet’s favour. Priscilla’s representatives alleged that Lady Harriet had not only allowed, but encouraged, the affair with the Earl. It was claimed that she had used her daughter to get close to the Earl herself, and had subsequently become jealous of their relationship and Priscilla’s pregnancy. The details put forward by Priscilla’s legal representatives were shocking; letters were presented to the court, allegedly from Lady Harriet to the Earl, in which:

She demanded £50 from Lord Kilmorey, recommending him to bring it secretly with this addition, “My daughter shall be ready for you in an hour, to do all that you wish. You will give me the consoling assurance that you continue to ride out with Priscilla. I would ardently wish to partake your pleasures.” – Dundee, Perth, and Cupar Advertiser – Friday 28 June 1844

Lady Harriet denied the allegations, and an account of events she put forward (via another daughter) in an advertisement in British papers suggested Dr Pinel was in the pay of the Earl.[12] Whilst this requires us to approach accounts he gave with a degree of cynicism, what is striking about the allegations against Lady Harriet is who supported them. Harriet’s own brother, the Earl of Orford, wrote to the court asking that Priscilla not be returned to her mother due to Harriet’s “cruelty” towards her.[13] Priscilla’s guardian, Captain Waldegrave, also opposed Harriet’s custody claim, whilst her brother (Harriet’s son) travelled over from England to testify against his mother, shockingly alleging that Harriet had planned to “remove his sister Priscilla to America, and to kill her infant”.[14] Priscilla herself told the court “she should prefer being placed in a convent to remaining with her mother, who had used her so cruelly that she had kept her bed three weeks”.[15]

As can be imagined, this story was pounced upon by the British press. A tale of sexual intrigue, sleaze and familial cruelty amongst the aristocracy had all the makings of a tabloid sensation. Papers across Britain and Ireland reported on the court case, whilst satirists and columnists weighed in to condemn the Earl and Lady Harriet.

The Parisian court ultimately ruled that Priscilla would remain in the custody of Dr Pinel until her 21st birthday just days later. And as soon as she was a legal adult Priscilla left France with the Earl, settling in Twickenham. Just weeks later she gave birth to their son; Charles Needham.

Many secondary sources have described Priscilla as the Earl’s ward, however I have not been able to substantiate this. There is no evidence of any acquaintance between the families prior to the meeting in Geneva, and it is not clear how this misconception emerged.

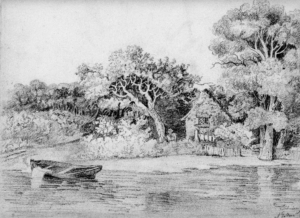

Not much is known about Priscilla’s life with the Earl after the elopement. They lived at Cross Deep House by the Thames at Strawberry Hill (since demolished, though what was once the grounds is now Radnor Gardens) before moving to Orleans House in 1846. Priscilla seems to have been inspired by the picturesque views of the area, recreating Twickenham riverside scenes in her sketchbook.

Priscilla developed a terminal heart disease at a young age, and sadly died in 1854 aged just 31. Her son Charles grew up to have an illustrious military career, and married the daughter of a wealthy Dutch aristocrat. His daughter Violet Needham, Priscilla’s granddaughter, became a highly regarded children’s author in the 1940s.

When Priscilla became ill Francis commissioned an elaborate mausoleum, with space for the couple and eventually their son Charles to be laid to rest. The imposing tomb was inspired by Egyptian architecture, and the interior featured a marble relief depicting a dying Priscilla being comforted by Francis and Charles. Francis not only spared no expense in its design, but would also move the mausoleum twice at great cost. It was initially constructed in Brompton cemetery, but when Francis moved to Woburn Park near Weybridge he brought the tomb with him. He then moved again, to Gordon House, and again had the mausoleum and his beloved Priscilla moved closer to him. This was the final move, and Francis was laid to rest alongside Priscilla upon his death in 1880. The mausoleum now stands in an enclosed garden in St Margaret’s. The spot for their son, Charles, was never filled and he was buried elsewhere upon his death in 1934.

Despite the wealth of media coverage of the affair, Priscilla’s perspective is frustratingly absent. It’s relatively easy to conclude from the available evidence that Francis sincerely loved her: he risked his reputation for their relationship, and chose to be laid to rest with Priscilla rather than either of his wives (or any of his many other presumed lovers). But how did Priscilla feel? Did she love Francis? Was she a naïve young girl groomed by a much older man? Did she run away with him just to escape her mother’s cruelty? Did she feel she couldn’t leave him after the enormous upset caused by their elopement?

The mausoleum takes on different meanings depending how you read the story. Is it a romantic monument to two lovers now together in everlasting rest? Or is it some sort of horrifying prison? The ultimate act of control from a domineering husband towards his much younger wife? We can only speculate, and keep searching for Priscilla’s perspective.

Martha Foster, the Earl’s 2nd wife

Just months after Jane died in 1867 Francis, now 79, remarried. Very little is known about his second wife, Martha Foster. Whereas the wedding of Jane and Francis in 1814 was announced in the national papers, it has not been possible to find any such announcements for his second wedding. This is all the more surprising given Francis was now the Earl of Kilmorey (when he and Jane married they had no titles of their own) and had developed a notorious reputation due to the affair with Priscilla and rumours of his interest in the occult. One might therefore assume there would be significant interest in his rapid remarriage, and curiosity about the new Countess of Kilmorey, yet I have not been able to locate any press coverage or announcements.

Turning to the archives presents some clues about Martha. The 1867 marriage certificate describes her as a spinster, and her father is listed as a Henry Foster, gentleman. The 1871 national census shows the couple living at Gordon House, St Margaret’s and lists Martha’s birthplace as Kent. It also reveals for the first time the striking age gap between the couple. In 1871 Francis was 83, and Martha just 29. Unfortunately it has not been possible to conclusively find any records on Martha prior to her marriage to the Earl (her name was very common at the time).

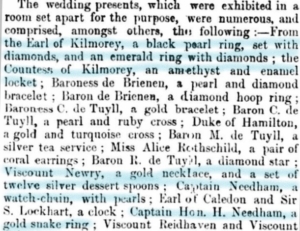

When Charles Needham, the son of Francis and Priscilla, married in 1874 both Martha and Francis attended. Also present were some of Francis’ children and grandchildren from his marriage to Jane. This is surprising given Charles was the illegitimate offspring of a scandalous affair. Their presence at the wedding and the lavish gifts the family gave the newlyweds, demonstrate that not only was Charles accepted by his father and Martha, but by (at least some members of) the wider Needham family.

Francis died at the age of 92 in 1880. Intriguingly none of the reporting of his death mentions Martha. In fact, some obituaries reference Jane, but not Martha.[16] She is also not referenced in his will. Compared to Jane and Priscilla, whose stories I have been able to somewhat flesh out, Martha remains a total mystery. A significant reason for this is presumably class. Whilst her father is listed as a gentleman, Martha does not appear to have noble connections. Jane and Priscilla both came from aristocratic families and had status independent of their relationship with the Earl; noble families track their lineage carefully and so there is a relative wealth of information on them. Martha, however, is an historical mystery, and what we do know of her raises far more questions than it answers. What was Martha’s life like before marriage? Given their age and class differences, how did Martha meet Francis? What did his children (most of whom were older than Martha) think of their new stepmother? What became of Martha after the Earl’s death? And, perhaps most confoundingly, what on earth did Martha think of the mausoleum in her garden that contained her husband’s long deceased mistress, and where he too intended to be laid to rest?

Concluding Thoughts

It is a sad truth, but in Western patriarchal societies the voices and life stories of women are all too often lost to history. To take one obvious example, the practice of women taking their husbands’ names makes them infinitely harder to track in the archives.

Our three women; Jane, Priscilla, and Martha, are rarely mentioned by biographers or contemporary journalists except in relation to Francis. Whilst this research has sought to redress this imbalance it has been constrained by the limited sources available. Such a situation invites us to craft our own narratives; when marginalised voices have been silenced by the passage of time and the biases of record-keepers, there is a certain empowerment to be found in trying to imagine forgotten lives and speculate with the scraps of information available. Mere crumbs, like knowing Jane was very close to her daughter, or that Priscilla liked to draw and once attended a ball with Princess Victoria, help us to envision the lives and personalities of these women and elevate them from being footnotes in the story of yet another ‘great man’.

I would like to thank Marion Russell, Philip Anley and the Anley family, Richard Needham, Earl of Kilmorey, Andrew George, Stephen Fielding, Emily Lunn and Vicky Phillips for their invaluable contributions to this project.

[1] Perthshire Courier – Thursday 27 January 1814 pg 3

[2] Belfast News-Letter – Friday 21 November 1828

[3] Deborah G. Wilson- Women, marriage and property in wealthy landed families in Ireland, 1750-1850, p. 135

[4] Morning Herald (London) – Friday 06 May 1836

[5] Leamington Spa Courier – Saturday 10 June 1848

[6] Leamington Spa Courier – Saturday 20 September 1851

[7] Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette – Thursday 01 August 1867

[8] Birth announcement Published: Monday 30 June 1823 Newspaper: Hampshire Chronicle

[9] Cork Examiner – Wednesday 26 June 1844

[10] Morning Post – Monday 02 June 1834

[11] Satirist; or, the Censor of the Times – Sunday 16 June 1844

[12] Morning Post – Thursday 05 September 1844

[13] Dundee Courier – Tuesday 02 July 1844

[14] Kilkenny Journal, and Leinster Commercial and Literary Advertiser – Saturday 29 June 1844

[15] Dundee, Perth, and Cupar Advertiser – Friday 28 June 1844

[16] Belfast Telegraph – Tuesday 22 June 1880