A hundred years ago John Alexander (Jack) Whitehead’s factory produced First World War aircraft. He was a flamboyant self-publicist, said to “possess all the racy and imaginative ability of the American storyteller”. One of his planes starred on a West End stage set. He changed the course of a West London river. He had grand visions for the peace-time future of flying but his own success in aviation ended with the war. Anne Logie writes about this colourful character.

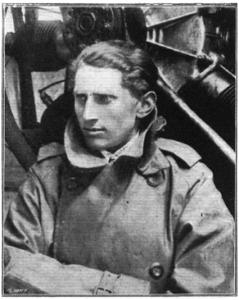

Portrait of J A Whitehead from “The New Dominion – The Book of Whitehead Aircraft, Richmond, Surrey”. Image used courtesy Richmond upon Thames Local Studies Library and Archive.

In August 1916 John Alexander Whitehead let it be known that he was buying Hanworth Park. He intended it for an aerodrome and had already submitted building plans to Feltham Council. The Whitehead Aircraft Company’s factory extension in Richmond had been opened with great ceremony by the Lord Mayor of London just weeks before, and it was less than a year since the company built its first plane.

Whitehead was a man of great vision and uncertain finance. He was also an avid and skilled self-publicist. In 1965 the aviation historian Bruce Robertson wrote: “Such was the flamboyant character of J A Whitehead, proprietor of the Whitehead Aviation Company, that now, precisely fifty years since the firm produced their first aircraft, it has proved difficult to separate fact from fiction …”. (“Whitehead Aircraft” – Bruce Robertson, published in Air Pictorial November 1965)

Born in London’s East End on 8 August 1875, Jack, as he was known, was the middle brother in a family of five sons born to George and Mary Ann Whitehead. George was a wine and spirit merchant who later founded the company George Whitehead and Sons, and Mary Ann’s father had created John Compton & Sons, suppliers of clothing to the armed forces.

Some time in the 1890s Whitehead set off alone for North America. Exactly what he did there remains a bit of a mystery but by the time he returned to England on 31 May 1914 he had become a cabinetmaker, an American citizen, and the divorced father of three children, of whom he had custody. On 29 August he enlisted in the Royal Naval Air Service as a Petty Officer Mechanic, but was discharged on 26 September. During his short service he had been to Dunkirk, where the Eastchurch RNAS Squadron (No 3 Squadron) under Wing Commander Charles Samson was based. After his discharge he got work as a carpenter at the Grahame-White Airplane Company factory in Hendon.

Despite having neither a company nor any evident experience of running a factory, in 1915 Whitehead managed to win a contract from the Ministry of Munitions to build six BE2b biplanes.

At some point Whitehead had met Edward Hewetson Heaps, who was one of the directors of the Richmond Automobile Company Ltd. The Richmond Automobile Company had a lease on 31 Townshend Terrace, Richmond, which had previously been used by the airplane designer L Howard-Flanders. As described in FLIGHT magazine (16 March 1912) Howard-Flanders’ premises consisted of a large hall, around 120 ft by 50 ft, which was to be used as an erecting shop “where four or more machines if necessary could be laid down at the same time”. There was also a machine shop in “an adjacent building”, and drawing and general offices above.

On the strength of Whitehead’s contract with the Ministry of Munitions Whitehead and Heaps went into business together. The Richmond Automobile Company Ltd was wound and up all its assets, including the lease on Townsend Terrace and the machinery in it, were assigned to a new company, Whitehead Aircraft Company Ltd, which was duly registered in May 1915 with Whitehead and Heaps as its two directors.

The whole enterprise had perhaps been somewhat touch and go. On 11 March 1915 Whitehead had applied to the US Embassy in London for an emergency American passport, declaring that he would return to the States as a permanent resident within one month, though he never did.

At this time airplanes were constructed substantially of a light wooden skeleton covered by a treated cloth skin. The Royal Aircraft Factory provided technical drawings and assembly instructions to its contractors, which was how Whitehead and his initially small team of carpenters were able to build the commissioned planes. Specialised metal parts such as guns and engines would be delivered from other factories to be fitted by the aircraft builders.

(More information about the Royal Aircraft Factory can be found in the Farnborough Air Services Trust briefings, e.g. http:// airsciences.org.uk/FAST_Briefings_09_RoyalAircraftFactory.pdf )

The period leading up to Whitehead’s acquisition of Hanworth Park will be covered in detail in a separate blog. Suffice it to say that Heaps resigned as company director in August 1915, the first of the commissioned BE2b biplanes was successfully completed at the end of October 1915 and the Whitehead Aircraft Company was awarded a further contract, this time to build Maurice Farman S11 Shorthorn planes, the first of which was completed in August 1916. Whitehead became something of a public figure and successfully mounted a campaign to have a day set aside to honour the mothers of those serving – or killed – in the war. The first such ‘Mothers’ Day’ was celebrated on 8 August 1916, Whitehead’s forty-first birthday. This event was touched on in the Environment Trust blog about the Hanworth Red Cross Military Hospital, “Boxing and Boating – Hanworth’s Red Cross Hospital” and there will be a separate blog about Mothers’ Day, so it will not have further mention here.

Building work at Hanworth went swiftly and FLIGHT magazine reported that on 9 September 1916 the pilot Herbert Sykes had moved his Martinsyde plane to Hanworth from its former hangar at Hendon. Getting Sykes as his test pilot was a coup for Whitehead; Sykes had daring-do and a popularity bound to bring additional notice to the Whitehead enterprise. He had obtained his Aviator’s Certificate in July 1915, having learnt to fly at the Ruffy-Baumann School, and was teaching at Hendon when he met Whitehead. From film and photographic records he appears to have been very small, which was useful in a pilot, and to have had a most engaging grin. There are many reports of him stunt flying as part of various Whitehead publicity activities, but he also undertook serious work as a test pilot. In June 1917 the engine of a plane he was testing failed and the plane nose dived from 200 feet, crashing with such force that the machine was partially buried. The unconscious Sykes was rushed to the Military Hospital in the park where he remained for ten weeks. Despite the severity of the accident he soon returned to work and in January 1918 was awarded an OBE “for courage in testing aircraft in spite of severe accidents”. The 2 May 1918 issue of FLIGHT reported the presentation of the OBE medal to Sykes at the Whitehead Aircraft Company works on 29 April. Despite the award’s official reference to multiple accidents, FLIGHT said that Sykes had made between three and four thousand flights but had only one accident.

2 – A rare picture of Herbert Sykes without his flying helmet and grin.

FLIGHT magazine 17 January 1918. Image courtesy FlightGlobal: part of RBI, reedbusiness.com.

Sykes can be seen briefly part way through the Pathe News archive clip “A Wonderful Airmen – Mr Sykes” https://www.britishpathe.com/video/a-wonderful-airmen-mr-sykes/query/air…. Note: “Airmen” is in the title, rather than “Airman”

Hanworth Park today is much smaller than the estate of over two hundred acres which Whitehead bought from the Lafones in September 1916, and smaller yet than the total area of land he ultimately acquired. In October 1916 he bought the Grange Estate, a large eighteenth century house known as The Grange with twenty-two acres of land. The house, which had been home to the Browell family, stood approximately on the west side of what is now Browell’s Lane, just opposite the point where the road cuts through to the Pizza Hut on Air Park Way.

The Grange Estate ran from the Longford River along the line of what is now Devonshire Court across to somewhere beyond what is now Browell’s Lane in the west. Following the line of the other arm of Browell’s Lane, all the land from Uxbridge Road in the east to at least Elmwood Avenue in the west, and south to Hounslow Road was also under Whitehead ownership through acquisition of the Hanworth Park Estate. The picture overall becomes complicated not only by further additions over the years but also by the government occupation of the land to the west.

Over the years Whitehead’s company also acquired Feltham House, the former home of ‘the Cabbage King’ Alfred W Smith, plus land totalling of over fifteen acres (September 1917), The Hollies (April 1918), Tudor House, Queen Elizabeth’s Gardens, and an area of land known as Bread, or Braid, Meadow (i.e. the land now bounded by Castle Way, Sunbury Way, and Felthambrook Way), totalling over forty-five acres of land (July 1918), The Rookeries, including over thirty-two acres of land (November 1918), and Parkside, a house with frontage on Feltham High Street and land behind backing onto the Feltham House grounds and running west almost to Elmwood Avenue (December 1918). (Note: dates given are all dates shown on mortgage documents.)

It must have been an unpleasant surprise for local residents to learn that Whitehead’s new works were to be built on the Grange Estate right at the end of Victoria Road. Parkland trees were felled, and two rows of huge sheds were built facing each other parallel to the Longford. The space between the sheds was concreted over, and a small line of track installed. The Grange itself was kept as offices and as a club house for the site workers, but the western sheds were built hard against it.

3 – This photograph shows the two rows of sheds with the houses of Victoria Road visible in the distance. The church spire opposite Feltham Station can be seen above the eastern sheds on the right of the picture. In the foreground is a temporary wooden bridge over the Longford River.

– image from the Clive Whitehead collection by courtesy of the Local Studies Collection, Feltham Library

The January 1987 edition of “Feedback”, the Thorn EMI Electronics Defence Systems Division’s local news sheet, includes an article by Reg Milner entitled “A Tour of the Whitehead Factory” with a map showing the Whitehead factory complex superimposed on the 1987 road map. To the east at the bottom of Victoria Road were two large buildings – one for offices, the other a sawmill and timber store. The gatehouse was on the corner of Victoria Road and Mono Lane, and on the north side of Mono Lane were two more large storage buildings. There was a canteen between the saw mill and the eastern erecting shed, and a power station behind the western erecting shed, roughly in line with Browells Lane. The last bay of the western shed was separated from the others and used by the Whitehead Flying School. When the 1987 article was published, all of Whitehead’s buildings, with the exception of a small gatehouse, were still standing and in use, but The Grange itself was gone. Milner comments that the buildings were laid out for the flow-line of production. Whitehead’s organisation of production both here and in Richmond was frequently noted for its smoothness and efficiency. The entire site has since been swept away by the buildings and parking lots along Mono Lane and Air Park Way.

In February 1917 the first Hanworth built plane was completed, a Sopwith Pup, registration number A6150. According to Milner eight hundred and twenty Pups were built at Hanworth and Whitehead’s combined factories built nearly 3% of all the aeroplanes produced during the war.

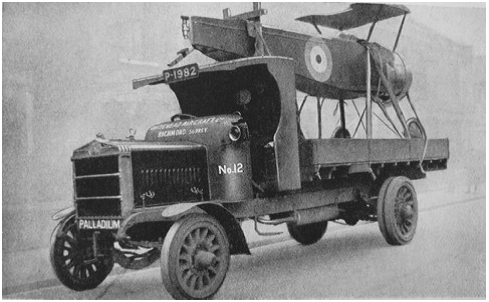

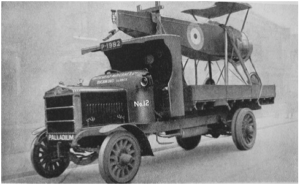

The Richmond factory continued in production. Planes were constructed in sections – fuselage, wings, tailplane, and undercarriage – and could be transported in sections for assembly elsewhere. The plane sections completed at Richmond were driven to Hanworth for assembly and testing.

.png)

4 – A Sopwith Scout mounted on a flatbed for delivery to Hanworth Park

– image from “The New Dominion: The Book of Whitehead Aircraft, Richmond, Surrey” used by courtesy of Richmond upon Thames Local Studies Library and Archive.

Sopwith Pups were initially called Sopwith Scouts. In his advertising and promotional material Whitehead called the planes he built Whitehead Scouts, creating the impression that his company had designed them. He never missed an opportunity to promote his brand. In May 1918 the American musical “Going Up” came to London’s Gaiety Theatre. Its set featured a full sized biplane. Whitehead managed to get the original prop plane replaced with a Pup from his factory, and it remained on stage, conspicuously marked ‘Whitehead Scout’, for the balance of the musical’s 574 performances.

Although Whitehead’s company did devise some aircraft designs it seems only one was built and it is unlikely it was ever flown.

Throughout 1917 Whitehead’s business continued to flourish. By August his company had around three thousand employees, was producing planes at the rate of about two per day, and was achieving national prominence.

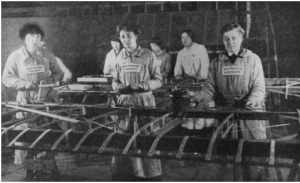

On 9 June 1917 a Pathé film entitled “Birth of an Aeroplane” showing the entire process of building a plane from felling the trees through to a flight over a Flanders battlefield was premiered at the Pathé Roof Garden Theatre. The factory footage was filmed in Richmond and the flight testing in Hanworth. Naturally it was Sykes doing the flying. The film showed the details of plane manufacture with “closest interest”. This film doesn’t seem to exist in its entirety any more but from the descriptions some unidentified footage in the Pathé archive could be part of it. It was said that the film gave a very good idea of the process of take-off in addition to the shots of Sykes putting the machine through its paces in the air. Busy workers were seen in the factory producing wooden and metal parts as well as fitting the engine, tail, etc. Women were shown at work in the fabric department, and it was noted that they each wore a conspicuous badge on either arm or breast saying “Whitehead Aircraft”. It is puzzling that the women were branded but not the men.

The Pathé archive clip on YouTube entitled “Battle Planes 1914-18” (called “Britain’s Mastery Of The Air” on the Pathé website) includes footage of the Whitehead factory. It opens with shots of the Scouts lined up at Hanworth, and then planes are seen being brought out from in front of the eastern shed. Note that the tails needed to be held up as planes did not yet have a wheel arrangement capable of keeping the tail off the ground. The film finishes with what appears to be the factory shift walking across the field in front of the planes. The man standing watching them might be the works manager. The clip “Women Aeroplane Workers In Factory”, though filmed elsewhere, gives a good idea of the assembly work. A similar Pathé film, “The Making Of An Aeroplane”, filmed at the Austin Motor Co Ltd in Longbridge can also be seen online. There is also online a Pathé film called “Women Factory Workers Say Merry Christmas” which shows women in the Whitehead factory with signs saying Merry Christmas (https://www.britishpathe.com/video/women-factory-workers-say-merry-xmas-aka-supply-of) Though the writing is indistinct, some of them are wearing the Whitehead Aircraft labels.

“Birth Of An Aeroplane” was not the only film featuring the Whitehead works. “A Munition Girl’s Romance”, starring Violet Hopson as Jenny the munition girl and Gregory Scott as the Head Draughtsman, went on general release in Autumn 1917. Also getting star billing was ‘Mr H SYKES (Britain’s most intrepid airman) by kind permission of Mr J A Whitehead of the Whitehead Aircraft Co.’. Advertised as ‘the film you’ve been waiting for’, it was shot in the Richmond factory and at the aerodrome, with the aerial footage being recorded from Sykes’ Martinsyde.

In July 1917 “The New Dominion: The Book Of Whitehead Aircraft” was published. FLIGHT magazine described it as “beautifully printed in an artistic type and illustrated by a large number of photographs”, worthy to be a souvenir of the aircraft industry as much as of Whitehead Aircraft Co. At least one of those photographs was faked. The picture captioned “A Battle-Plane Over Hanworth Works” is the photograph reproduced as No.3 in this article with the addition of a soaring biplane in the middle of the sky. Very impressive it looks too. The booklet included a section about the Whitehead flying school. Seemingly very much in line with Sykes’ view on the importance of theory before flight, Whitehead student pilots would learn about aircraft construction before launching into the air in a Caudron GIII. The booklet was subtly updated between its first and third editions with new photographs to make the undertaking appear larger, more up-to-date, and more military.

5a Women making airplane wings

.– image from “The New Dominion: The Book of Whitehead Aircraft, Richmond, Surrey” (first edition) used by courtesy of Richmond upon Thames Local Studies Library and Archive.

5b Women making airplane wings

.– image from “The New Dominion: The Book of Whitehead Aircraft, Richmond, Surrey” (third edition) used by courtesy of Richmond upon Thames Local Studies Library and Archive.

Whitehead participated in a number of charitable events which gained wide publicity. When the 1917 Royal Horse Show for benefit the RSPCA was cancelled he offered the promoters the use of Hanworth Park and promised to provide assistance in putting on a “great aircraft festival” and garden party to be held on 10 and 11 August. It was noted in the press that he was already “a liberal donor” to the Fund for British Horses. He donated to the Boys Naval Brigade and the Girl Guides. In September 1917 Queen Amilie of Portugal, president of the Richmond District Girl Guides, visited the company’s works and was then entertained at Beccleuch House where the Guides put on a display. There is a short Pathé film of Queen Amilie at Beccleuch House, and Whitehead can briefly be seen at her side as they descend the steps to the garden. http://www.britishpathe.com/video/queen-amelia-of-portugal-at-richmond

Beccleuch House was a prominent eighteenth century house which until 1938 stood by the Thames in what is now the open space downhill from Terrace Gardens on Petersham Road, Richmond. Whitehead moved his family there some time in 1917 and was renting it at a rate of £1,000 a year. He was taking a salary from his company of £3,000 a year plus £1,000 expenses. By way of comparison, in 1915 the expected annual cost of the thirty-bed Red Cross military hospital in Hanworth Park House was only £3,800.

Whitehead was achieving remarkable things in business, looking after his workers well, donating handsomely to charity, but he was also living lavishly. In “The Whitehead Aircraft Story” Bruce Robertson quotes Squadron Commander R E Nicoll, RNAS, of the Admiralty’s Air Division recalling of his visit to Whitehead “It was quite an education to visit him. His office contained an enormous desk, a period piece of untold value, and a carpet you sank in to up to your ankles! If you were one of his special visitors an enormous trolley would be wheeled in by a butler containing every conceivable drink as well as the finest cigars.” Whitehead insisted that this lifestyle was a necessity. He needed money for his business, and in order to make contact with the kind of people who might invest he needed to be where they were, to live as they lived. He later estimated that he was living at a rate of £10,000 a year.

Whitehead’s constant need for money to expand his business led him to repeatedly restructure his companies, replacing one with another in order to bring in more capital through the issue of shares. It was seen as a measure of his business’ success that the wages bill had gone from £7 in the company’s first week up to somewhere between £4,000 and £5,000 per week. In the Autumn of 1917 he sought to obtain further capital by issuing shares in a new company, Whitehead Aircraft (1917) Ltd.

Whitehead’s vision went beyond building planes for the war effort. He imagined Hanworth Park – or Whitehead Park as he sometimes called it – as a great aerodrome. He believed in a future with frequent scheduled flights to all the major cities of the world. He would have not only a factory and a flying school, but an airport from which his own planes would fly.

Money aside, one very immediate obstacle to such a plan was the Longford River. To fly his planes he needed unrestricted take off and landing areas. The Longford River flowed behind the eastern shed but then, as can be seen in picture 3 above, it curved west, blocking access to the sheds, before turning south east across an otherwise perfect taxiing area. Nothing daunted Whitehead set about changing the course of the river. A culvert was built from a point near the eastern shed running in a straight line down nearly to Hanworth Park House. The level of the river had to be dropped several feet below ground level for the length of the culvert and then raised to the surface again on the far side of the flying field to continue its journey towards Hampton Court Palace. This was a major feat of engineering, involving the creation of a reverse siphon by the Resident Engineer, Mr Seeley Allin, and the labour of German prisoners of war. The prisoners were housed at the Feltham Borstal, conveniently close, however their use in this project was perhaps open to question, as prisoners of war could not be engaged on war work. Whitehead Aircraft was a government controlled establishment entirely dedicated to producing planes for the military, but somehow the prisoners’ work was allowed.

Traced against a present day street map, the original course of the Longford before Whitehead’s culvert ran west along Browell’s Lane and then from the roundabout south east down the length of Forest Road and straight on down the side of the road that leads to Hanworth Park House.

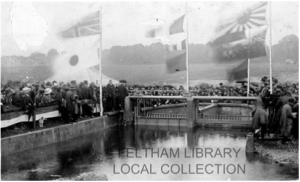

On 16 October 1917 the new Lord Mayor of London, Col. the Rt. Hon. William H Dunn, Bart., opened the aerodrome and set in motion the culvert mechanism, an event which was reported widely throughout the country. As described in the Whitehead company’s club magazine, ‘Whitecraft’, this was quite an event. The Mayor, accompanied by two Sheriffs, initially inspected the Richmond factory, including the workers’ canteen and the club house. “A picturesque guard of honour” of Richmond Girl Guides drew up in Sheen Road and the “distinguished” company departed for lunch at Beccleuch House. The distinguished company included forty-eight persons of prominence – mayors, aldermen, sheriffs, councillors, members of Parliament, Canadian and Australian agents-general, Whitehead’s father and uncle, and Mr H G Wells. In the course of the speeches which followed Whitehead somewhat bizarrely referred to his “two or three thousand loyal employees” who were doing their best to supply airplanes. The Mayor noted that he had known Whitehead’s father, George, for many years. H G Wells was called upon to make a speech and reminded all of the hardships of those in the field of battle. After various other speeches the party was conveyed by car to Feltham, where in hard rain and wind gusting to over forty miles an hour the Mayor set the mechanism in motion. Despite the weather Sykes put on his customary aerial display, reported in FLIGHT (18 October 1917) as “looping the loop many times and liberating showers of leaflets”, before turning off his engine and gliding in to land “the machine rocking like a ship at sea”.

The event, complete with Sykes, can be seen in the Pathe film “River Diverted at Harmworth Park 1917” (note that the title mistakenly refers to Harmworth rather than Hanworth Park) https://www.britishpathe.com/video/river-diverted-at-harmworth-park

6 – The ceremony for the diversion of the Longford River. The Lord Mayor of London in his ceremonial hat is standing by the sluice gate on the left, and behind him, bare headed, is J A Whitehead. This sluice is now almost hidden behind a small parking lot on the north side of Browells Lane near Cineworld.

– image from the Clive Whitehead collection by courtesy of the Local Studies Collection, Feltham Library

Part of Whitehead’s vision for the future was outlined in a speech reported in the 7 July 1917

edition of the Middlesex Chronicle. Hanworth would become the principal depot for aerial postage between the UK and Europe, with hundreds of aircraft coming and going everyday. As a result of the air traffic the local railway would be electrified, with trains every ten minutes connecting with the District Railway, giving access to anywhere in London and its districts. Local businesses would double or even quadruple in value within two or three years, and the population would similarly increase. Heavier than air machines would be able to carry more than their own weight, and would fly post and passengers at 150 mph to anywhere in the world, including New York – a mere sixteen hours away. Apparently he did not envisage that had his park become a major airport Feltham and Hanworth would have been concreted over, or if he did, he wasn’t letting on.

The same issue of the Middlesex Chronicle contains a light-hearted story about a giant carp

supposedly resident in the recently drained Hanworth Park pond. The article comments “before proceeding further it is well to remind readers, in order that they may better appreciate the narrative, that Mr Whitehead possess all the racy and imaginative ability of the American storyteller.” That talent must have contributed greatly to his ability to win people to his schemes. His reported speeches tend to combine a vision for the future, praise for the workers responsible for his success, a reminder that the labours and trials of civilians were as nothing to those of the men fighting and dying on the front, an exhortation to work harder towards future goals, and, depending on the occasion, a call on his audience to support those at the front by investing in his company so that he can build more planes. Printed materials promoting his company were free from any element of personal modesty, and his qualities and achievements were described in near hagiographic terms.

Although Whitehead continued to spend and expand, the wind was blowing less strongly in his favour. The 28 February 1918 edition of FLIGHT reported questions which had been raised in Parliament with regard to the finances of the company. Sir Watson Rutherford asked whether the Air Ministry had refused to recommend a proposed increase in the company’s capital through the issue of further shares. Sir Watson pointed out that the company had already doubled its output and acquired additional land and could easily obtain a further £750,000 to enable it to again double its output. Major Baird replied that the Ministry of Munitions would not oppose any reasonable scheme for raising capital by public issue, but that it could meet its needs from existing facilities without any need for Whitehead Aircraft (1917) Ltd to expand. He explained that the company had asked consent for the issue of further shares so it could raise capital to pay off its debt to the Ministry of Munitions for money already advanced. Sir Watson then asked Bonar Law, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, why the proposed increase was being refused as not in the public interest, adding that the company’s wages bill was now £11,000 per week. The Chancellor replied that the company had made amended proposals which had been agreed but for “one small item”.

As a government controlled establishment Whitehead Aircraft (1917) Ltd was under tight financial restrictions. To prevent wartime profiteering there were limits on the amount of profit the company could make, and the Government would only approve the issue of new shares if such a move were deemed to be in the national interest. There were also cashflow problems. Payment for planes was only made on delivery and acceptance, which meant that manufacturers had to deliver their planes to a Government designated location where each plane would be inspected and tested. In the early days limited testing facilities resulted in considerable delays in testing, and therefore delayed payment. To try to reduce the delay in the face of wartime demand the Government created more ‘acceptance parks’, which were often built near suppliers. In addition to delays in acceptance of their planes, aeroplane manufacturers suffered from delays in the supply of materials and components, especially engines and guns. Caught between their suppliers and the Government accounting system companies had to manage all the ongoing expenses such as staff wages. When these inherent industry problems came up against Whitehead’s unquenchable desire for expansion financial difficulties were inevitable. The company had already received an advance of £30,000 from the Ministry of Munitions, presumably the debt referred to by Major Baird in the Parliamentary debate, and repayment of that debt was cutting into the company’s profit margin.

It is difficult to tell from this distance whether a buoyant nature enabled Whitehead to believe that good news was just around the corner or whether his expressed belief in the inevitability of expansion of the air industry blinded him to the difficulties ahead. For the time being luck was with him, and in March 1918 the Government authorised the issue of further shares to bring the company’s capital up to £1,000,000.

To be continued….

This blog is part of an ongoing project. I would like to thank James Marshall and his staff at Feltham Library Local Studies and also the archivists at Richmond upon Thames Local Studies Library and Archive for their continuing assistance and endless patience. Additional thanks to Roy Swales at the Archive Department and Research Centre of the Fleet Air Arm Museum for information about Whitehead’s brief service with the RNAS.

Notes:

It is worth visiting the RAF Museum or Brooklands Museum to see just how extraordinary planes were in the early years. Photographs do not convey the complexity and the delicacy of construction nor the courage of the people prepared to pilot the things.

The RAF Museum’s London site has a BE2b plane, the first type commissioned from Whitehead, which may also be seen on their website https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/research/collections/royal-aircraft-factory….

The Imperial War Museum has an image of a Farman Shorthorn on its website https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205127666 .

Brooklands, in addition to its exhibition of planes from various eras, has a display showing parts of the aircraft factory process.

A film of an early French aircraft construction can be seen on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eCZ1EIs4ohE

This Pathé clip shows a factory much more like Whitehead’s. Note the numbers of women workers. https://www.britishpathe.com/video/women-aeroplane-workers-in-factory/qu… .

Whitehead’s factory appears in a few brief clips in the Pathé archive. This clip shows completed “Scouts” being brought out from the hangars in Hanworth Park https://www.britishpathe.com/video/battle-planes/query/Hanworth )

Sources

This being a blog rather than an academic paper, I am listing only principal sources and then only in connection with certain items.

Whitehead’s service with the Royal Naval Air Service – National Archives file Reference ADM 188/560/185. Additional information supplied by the Archive Department & Research Centre of the Fleet Air Arm Museum.

‘Whitecraft’ and ‘The New Dominion: The Book of Whitehead Aircraft, Richmond, Surrey’ (first and third editions) – copies held in the Richmond upon Thames Local Studies Library and Archive. (‘The New Dominion’ is filed under “Vertical files – Townshend Terrace 1-41”.)

‘Feedback’ is in the collection of Feltham Library Local Studies, as is the Clive Whitehead collection of photographs, together with numerous large historic ordinance survey maps of the area.

FLIGHT magazine is available online at https://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/

The Whitehead Aircraft Story – Bruce Robertson, published in Aviation News 12-15 February, mentions the use of the Whitehead Scout in the Gaiety Theatre production of ‘Going Up’. Additional information about the production from Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Going_Up_(musical) (accessed 17 September 2018