The Sir Joseph Bazalgette Mausoleum

Zoe Lawrence has delved into the history behind the mausoleum of Sir Joseph Bazalgette, a site which Habitats & Heritage is working to conserve.

The Bazalgette Mausoleum can be found in the small, but beautiful churchyard of St Mary’s in Wimbledon. It’s tucked away towards the rear under a canopy of trees. But it hasn’t always been Bazalgette’s mausoleum.

The first documented reference of this burial place was on the 31st of October 1801 when the Last Will and Testament of John Anthony Rucker was made (proved in 1804). The first page reads: ‘they be directly buried without any pomp or unnecessary parade and that a piece of ground may be purchased in an open church yard preferring Wimbledon Church yard if it can be purchased there should just have made such purchase in my lifetime in which a vault shall be built wherein my body shall be laid’. The will of John Anthony Rucker is fascinating from several perspectives. First of all, it is 17 pages of continuous handwriting without any use of punctuation. John Anthony Rucker, though he never married, had extensive family through his brothers, nieces and nephews. He was a wealthy man and many people benefited from his passing by receiving large sums of money or pensions. His will distributes in excess of £80,000 in cash or pensions which would equate to over £3.2m today. He took pains in his will to make clear that sums of money bequeathed to women were for their ‘sole and personal use’ and not the property of or control of their husbands. All estate, both in England and the West Indies was left to his nephew Daniel Henry Rucker, then in his 40s.

So, who was John Anthony Rucker? He was born in Hamburg, Germany in 1719. He came to England sometime after 1727 and was naturalised in 1744 dropping the umlaut on his name. Rucker was a trader and businessman, and a partner in a firm of Hamburg merchants at Laurence Poutney Hill in the City of London during the 1740s. In the early 1760s he formed a partnership with two calico printers, Nixon and Amyand. He was also co-owner with Robert Harvey of ‘slave-property’ in Grenada. With John Harvey he had formed a partnership in 1763 to invest £20,000 in land and plantations in Grenada. He owned 1672 acres of land in St Patrick’s in Grenada, and despite his potentially more positive view of women, owned over 700 slaves. Making the bulk of his wealth from the sugar plantations of the West Indies and the slave trade, in 1770 he was able to become the co-founder of a banking firm that evolved into Dorrien, Magens and Mello, a predecessor of the Royal Bank of Scotland.

Rucker’s legacy is still apparent on the London landscape. In 1786, with the proceeds from the sugar trade in the West Indies, Rucker bought land and property at West Hill, East Putney in London. He demolished the existing mansion designed by Capability Brown, and built Melrose Hall, designed by Jesse Gibson who also designed Rucker’s original mausoleum in the church yard. After Rucker’s death, Melrose Hall was sold in 1825 in a public auction to George Granville Leveson-Gower. This was a likely attempt by Daniel Rucker to release cash to avoid bankruptcy, but alas he was adjudicated bankrupt six years later on 22 November 1831. In 1863, Melrose Hall was sold again to a charity and became The Royal Hospital for Incurables. A title that didn’t give much hope to those referred there. The hospital is now the Royal Hospital for Neuro-disability and much of the building and grounds are retained and are maintained to a high standard.

Another piece of Rucker’s legacy can be found in Morden Hall Park, South London. A small section of the River Wandle was recut and widened to better supply the textile printing factory owned by Rucker, Nixon and Amyand. This section of the Wandle is still referred to as Rucker’s Cut. In 1770, Rucker is also thought to have built Wandle Villa behind the calico mill at Phipps Bridge, which is still there today.

John Anthony Rucker died in 1804, and the wishes in his will were carried out. It is thought that his choice of Wimbledon was owed to its proximity to Melrose Hall, from the grounds you would have been able to see Wimbledon, across the park and the church in the distance, just a couple of miles away. A mausoleum was erected and there he laid. The original structure designed by Jessie Gibson is thought to have included a pyramidal obelisk and room for eight other burials, suggesting that other members of the Rucker family would be buried with John in due course. This did not to come to pass with members of the Rucker family found buried in numerous cemeteries across London and Kent.

Between 1804 and 1888 London changed dramatically. In 1801, when the first reliable modern census was recorded, there were about 1m people living in London. By 1891, at the time of Joseph Bazalgette’s death, there were in excess of 5.5m people living in the capital. The mortality rate in England and Wales in 1850 was more than double what it is today per 100,000 people (2000+ deaths per 100,00 compared to 890 per 100,000 people). Direct comparisons are difficult because of population growth but the main causes of death in the 1800s were infectious diseases including tuberculosis, smallpox, influenza and cholera. It is thought that over 20,000 people died in the cholera outbreaks in London between 1832 and 1848. Child mortality in Victorian London was high with approximately 30% of all children dying before the age of 5.

Traditionally, like John Rucker, before the population growth and corresponding number of deaths, people were buried in their local parish churches. This was a steady flow of income for the churches which they did not want to stem. It soon became apparent across London that the parish churchyards were overflowing with corpses. Something had to be done. In 1832, coinciding with the first cholera epidemic, saw the formation of the General Cemetery Company followed by legislation passed in 1852 to limit church burials. Satellite cemeteries around London were gradually established the first being Kensal Rise, in 1832 but soon others including Highgate and Brompton were available. These are referred to as the Magnificent Seven. A dedicated necropolis train was also built from Waterloo Station to take coffins to Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey which at one time boasted to be the largest cemetery in Europe.

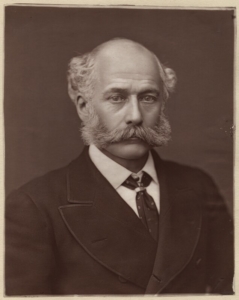

This is all relevant to Joseph Bazalgette on several fronts. In 1854, after numerous cholera outbreaks in London and many thousands of deaths, John Snow evidenced that the key source of the cholera epidemics was waterborne. Around the same time Joseph was commissioned to assess the sewers in London, and following the Great Stink of 1858, his new closed sewers were implemented. The new sewers which extended for many miles and included several elaborate pumping stations almost eliminated cholera and other waterborne diseases saving many Londoners’ lives. The public health of London advanced significantly as a result of his endeavours, and they continue to do so to this day. Sir Joseph as well as being famous for being the civil engineer of the London sewers is also famed for the Albert and Victoria Embankments, and Putney, Battersea and Hammersmith bridges.

In 1873, a few years before the London sewers were completed, Joseph Bazalgette moved into a house on Arthur Road in Wimbledon, just across the road from the parish Church of St Mary’s. The church records from this time show frequent and regular cash donations to the church made by Sir Joseph and Lady Bazalgette and one of their daughters referred to as Miss Bazalgette. Some of the larger donations and subscriptions made for various good causes were £10, which would be over £1000 in value today. These would be very welcome sums for a small parish church, with dwindling income from burials. However, what is most notable from the church records is the Vicar and Rural Dean’s address which provides an interesting commentary on the burial space at the churchyard. He states ‘that the churchyard being full, and it became necessary to make immediate provision for the burial of the dead. Votes in favour of a cemetery, a suitable piece of ground, about 20 acres, in South Wimbledon (between the Gap and the Woodman Inn) should be purchased for the cemetery’. In 1874 the Vicar records that ‘the Burial Board have now completed the steps necessary for the formation of the New Cemetery which will probably be available in about six months from this date’. However, this was unfortunately delayed, because works needed to be completed to move a sewer from across the new cemetery plot.

The church records 1876 continue to say ‘the delay in opening the New Cemetery has been the source of some anxiety and difficulty – the old churchyard at St Mary’s being full. An attempt was made to enlarge it by the purchase of an adjacent plot of land rather less than an acre, but as this would cost (including the wall and preparation of the ground) about £2000, towards which we have only obtained contributions and promises amounting to about £600, the matter remains in abeyance. It would give much satisfaction to many if this work could be completed, but there seems no way of doing it, unless a few of our wealthier residents will combine to purchase the additional plot, and sell to the parish, from time to time, as much as there are funds to pay for. Meanwhile the new cemetery is advancing and will be ready it is expected, in the Autumn of the present year’. The cemetery on Gap Road in Wimbledon did open in 1876. From maps dating to that period there is no evidence that the additional land was purchased, it may not have been needed in the end.

The next event in this tale concerns Joseph Bazalgette’s son, Charles Norman, who died in 1888 at the age of 40. Imagining Sir and Lady Bazalgette’s predicament, bearing in mind that at that time burials were the norm and cremations a peculiar foreign custom, they would have wanted to bury their son. They were fully subscribed to the local parish church which was near their house. The churchyard was full to overflowing, what could they do?

All the property, including it is assumed the mausoleum, belonging to John Anthony Rucker was inherited by Daniel Henry Rucker as stated, but not specified, in the will. Daniel’s company was adjudicated bankrupt in 1831 and he died in 1846. The bankruptcy order concluding matters is dated 11 March 1898. There are a couple of possibilities here. The Official Receiver, Mr Edwin Leadam Hough may have had authority to sell the mausoleum as part of bankruptcy proceedings. It’s unlikely it was sold to the Bazalgettes by the Rucker family. Alternatively, the church may have considered that the mausoleum had been left unattended for 84 years, there had been no subsequent burials of other family members in the mausoleum, and person who had possibly inherited the plot had died and their assets were held in bankruptcy proceedings. The Bazalgette family were upstanding in the local community and generous donors to the church.

The records for this period unfortunately run dry. Those at the National Archives at Kew and the Surrey History Centre in Woking hold no account of any transaction that may have taken place to transfer the property from Rucker to Bazalgette. However, we know that this did happen, and that the mausoleum was refashioned, and a rectangular obelisk replaced the previous pyramidal structure. There are new engravings and the remains of six other Bazalgette family members are now inside the mausoleum including Joseph and his wife. It’s also suspected that the mausoleum may have been enlarged at the rear. The re-use of burial plots is not uncommon particularly after this length of time. Today there is acceptance that a grave plot can be re-used after 75 years. The precedent may have been based on custom and practice of times gone by. The vicar of St Mary’s may have considered it a reasonable use of the space and a way to thank and commemorate an esteemed local man and his family, to allow the burial at the church and not refer them to the cemetery on Gap Road. It does appear odd initially that there seems to be an imposter in the mausoleum when you peep through the iron gate at the names seen in the coffin cradle – a Rucker clearly marked amongst the Bazalgettes. But the decision to do this, within the context of the times, is not unreasonable, but a practical solution.

I would like to thank Justine Pearson of the Surrey History Centre for her support, diligence and scrutiny in searching for records to support this research. The document people at the National Archives in Kew who helped me find what I needed. But I think the greatest insights were from the Vicar of Wimbledon in the 1870’s, Rev Cannon Haygarth whose address in the church records that he painstakingly prepared each year, helped set the scene in such detail as to best understand the circumstances of the time, and how this unusual arrangement may have come about.

Zoe Lawrence

August 2022