Phillip Alwyn Wheldale Roffey – A Biography by Becca Aveson

Habitats & Heritage volunteer, Becca Aveson has delved into the story behind the architect of the St. Leonards Court air raid shelter, Philip Roffey.

Phillip Alwyn Wheldale Roffey designed some of Richmond borough’s Art Deco style apartments found in Mortlake, East Sheen and Richmond. St Leonard’s Court and Deanhill are located in the East Sheen and Mortlake area, whilst Queen’s Court can be found on Richmond Hill. Whilst there is little known about the latter, and its link to Roffey, the former two are both attributed to him, and all three share similar design features and typical of1930s estate design in London.

What makes these buildings special lays beneath the surface, and if you weren’t looking out for it, you’d miss their markers. Both St Leonard’s Court and Deanhill contain relics of the second world war history in the form of air raid shelters, which were used regularly by residents throughout the war. The presence of the shelters makes the estates all the more interesting as they not only boast the style and luxury of 1930s design, but also demonstrate the civil infrastructure being built on the eve of the war to protect residents in the event of aerial bombing raids. The survival of the shelters offers an opportunity for the people of today to walk in the footsteps of former inhabitants in a series of rooms which do not reflect the glamourous vibes of the building above the surface. This article will delve into what we know about the life of Phillip Roffey, and how his architectural design fits into Greater London’s social and second world war history.

Early life and Inspiration:

Roffey was a local architect based in Putney Hill, and worked alongside Richard Brocklesby, who was the son of, Mr John Brocklesby (see the society here), a prominent architect in the Merton area in the first decades of the 20th century. Brocklesby’s work included restoration projects as well as contemporary builds which created many public spaces which are still in place today. Brocklesby’s works are associated to a trust which sought to rejuvenate Merton and bring more modernised and stylish housing to the area. Brocklesby took influence from the arts and craft style which dominated art and architecture at the time.

A three-year-old Roffey is recorded in the 1911 census as living with his parents, younger brother, and aunt in the residential area of Edgware. Roffey grew up in a time when London’s railways and underground were being developed and extended to make the city more accessible to suburban areas like Edgware. The relative closeness of Edgware to the centre of the capital would have given him exposure to the ever-expanding city in his childhood. Roffey’s father was a builder which offers a clue to where his later interest in architecture may have materialised.

Career and the Art-Deco influence:

Roffey was a member of both the Chartered Institute of Surveyors and Royal Institute of British Architects. In the earlier part of his career he was a joint director of an architectural firm in Putney with one Mr Brocklesby. This partnership ceased in 1936. Roffey and Brocklesby worked together on the original plans for the St. Leonards Court site which were ultimately rejected, and new plans drawn up. Brocklesby involvement in the early stages of the St. Leonards would suggest that the building seen today was not only Roffey’s design but also Brocklesby’s influence too.

Art-deco estates are common in many residential and inner areas of the capital though London was relatively slow in adopting the architectural style. Many other major world cities had started building art-deco structures as early as the mid-twenties when the world experienced a cultural boom following the Great War. Most art deco design is associated with the mid to late 1920s, but British artists and architects were slow to adopt. Whilst Roffey’s work was at the tail end of the movement, he fell right into the thick of it when it did eventually become popular in London. Today, these buildings still present an interesting sight to behold when wandering through the streets of both Central and Greater London. One London resident, Claire Bennie, who is particularly interested in the beauty of Art Deco architecture in the capital, has compiled an online database of examples of theses (see here). Roffey’s works are unfortunately not mentioned or referenced, but there is a multitude of examples that show striking similarities to Roffey’s key design features. If we use St Leonard’s Court as an example (fig. 2) it shares resemblances to many of the other buildings listed in this archive.

Despite their glamourous exteriors, Roffey’s estates hold a key to part of London’s social history; below the surface of both the Dean Hill estate and St Leonard’s Court, there are the remnants of two Second World War air raid shelters, built on the eve of the war. As tensions built between European and global nations during the 1930s, there was concern that the air raids experienced during the Great War could return. The government published advice which detailed how communities and local bodies could make current infrastructure safer during what was a time of uncertainty to protect residents.

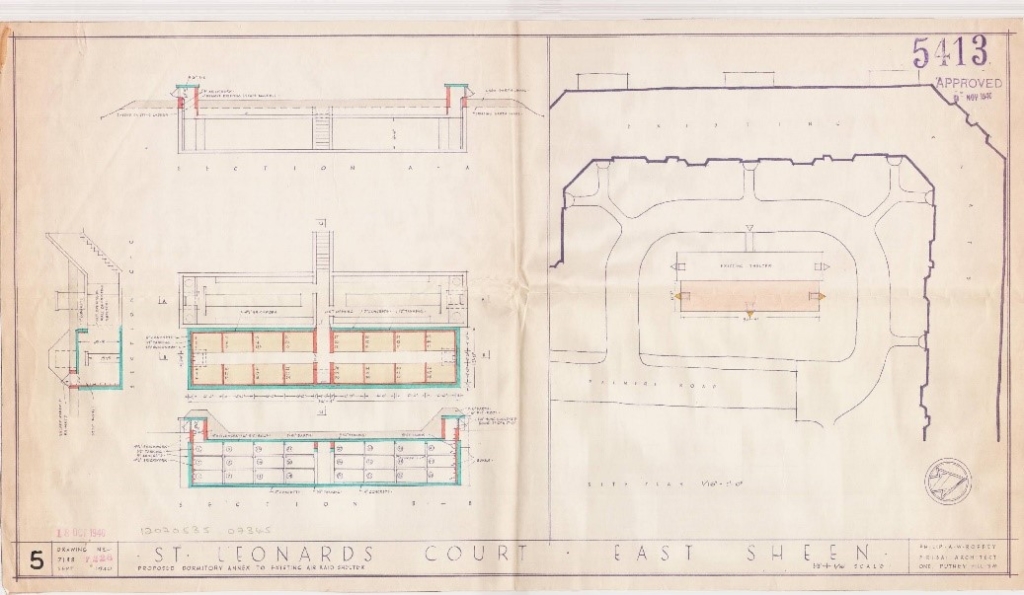

Whilst the motivations behind the inclusion of an air raid shelter at St. Leonards and Deanhill are more speculative than definitive, it highlights the desire to build such infrastructure for residents living in private housing. The shelter at St Leonard’s was built in two stages, the plans above show the addition of the sleeping annex which extended the shelter to include space for bunks in 1940, at the height of the nocturnal Blitz. Roffey put the inhabitants of his buildings at the centre of their design, and the air raid shelters were no different. The small details such as numbered bunks, separate rooms for men and women, and chemical toilets would have given users some sense of comfort when they would have felt most vulnerable. In fact, the chemical loos would have been among the first of their kind to be used in Britain. There is a virtual tour of the shelter at St Leonard’s Court available here, but the true impact of the site can only be gained through visiting in person.

War-time Britain changed Roffey’s working dynamic. Like many, his life moved to the countryside in Dorset to escape the blitz in London and other UK cities. In this time, he had a daughter, Joanna, with his wife and remained in Dorset throughout the war. After this time, he and his family spent some time in Durban, South Africa before returning to Surrey in 1953. He bought a 17th century manor house in Epsom, Surrey where he intended to rekindle his architectural work, living there with his family until his death in 1966. There is little know about other works which have been accredited to him, but the builder who put his designs into being, F G Fox, continued to develop housing following the war in around the East Sheen area. These would have provided new housing for the area which was substantially bombed during the blitz. Fox’s new builds were not designed by Roffey, nor can be classed as art deco. They would nevertheless have provided much needed homes for residents following a turbulent six years at.

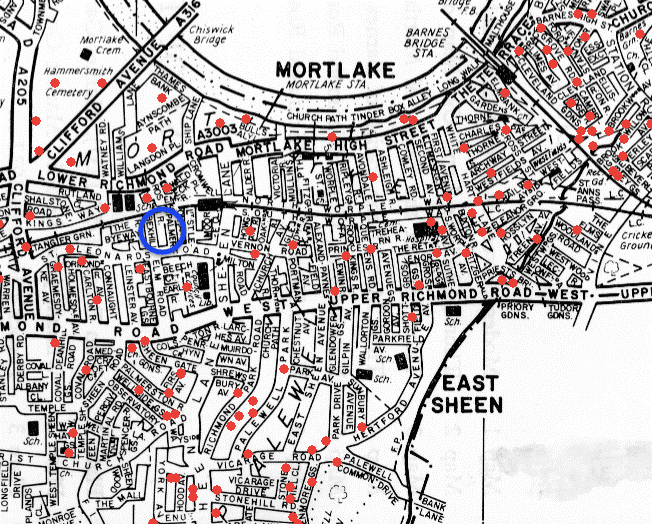

Roffey’s work is something of a masterpiece for the East Sheen skyline. His buildings embrace the British take on the Art deco style from the late 1930s and stand out in an area amongst Edwardian and post-war housing stock. The map above shows the degree of bomb damage to the East Sheen and Mortlake areas, with all explosions marked by red dots. St Leonard’s Court is highlighted on the map using the blue circle. This map not only shows the damage to the area, but just how close these buildings were to the perils of war. The estates’ wartime heritage makes them all the more special to the residents of today by offering a window into what typical everyday life was like for their predecessors during the war. The shelters at both St Leonard’s Court and Deanhill are among a remaining handful of surviving and still accessible, purpose-built air raid shelters that are largely intact. The interiors of the shelters demonstrate a less than glamourised way of living within a new block of flats in the war years, and whilst they wouldn’t have been in constant use, they demonstrate a way of life that not many of the current residents will have experienced within living memory.