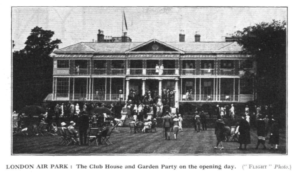

The Club House, Hanworth Park on the opening day. (Flight 11 October 1929). The Club House is now known as Hanworth Park House.

The Club House and grounds from the air (Flight magazine 11 October 1929)

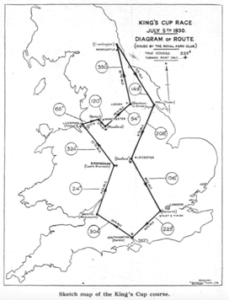

In 1930 Hanworth hosted the most famous air race of the day – the King’s Cup. The race had started the previous two years at Heston (1929) and Hendon (1928). First held in 1922, this was a 750 mile race around Britain in a single day, with stops for refuelling – a bit like an airborne Formula One. It was recognised as a testing place for new machines and a proving ground for amateur pilots and usually attracted all the famous aviators of the day. In 1930 most of the aircraft were biplanes which were handicapped on speed, with the slowest starting first.

Front cover of 1930 King’s Cup programme, signed by the winner, Winifred Brown (Source: HOUNSLOW LIBRARIES LOCAL COLLECTION, FELTHAM LIBRARY)

Sketch map of the King’s Cup course, undated, probably 1984 by Ken Mason in connection with his lecture to the Honeslaw History Society. (Source: HOUNSLOW LIBRARIES LOCAL COLLECTION, FELTHAM LIBRARY)

On 5th July, an almost perfect summer’s day at Hanworth, a record of 96 entered the race, and, as the contemporary account says, 61 managed to complete the course, returning to Hanworth before 8pm the same day. This was the largest entry and the largest number of starters and finishers.

The King’s Cup was a race for men and women to compete on equal terms. Ladies Races had become a feature of air race meetings, and women daring to get in an airplane let alone take controls was still noteworthy.

Of the 96 entries at Hanworth, six of them were pilots from the fair sex, as Flight magazine called them. Among these six were some of the most famous women aviators, or aviatrices, as they were described at the time. They included the Irish Ladies: Lady Bailey and Lady Heath, but also Winifred Spooner, the only woman to earn her living as a pilot in the early years of aviation, and Winifred Brown.

88 [of the 96 entries] actually crossed the line when the starter dropped his flag

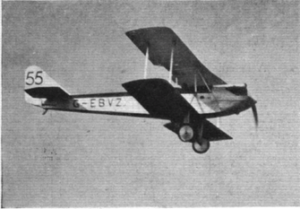

Winifred Brown’s Avro Avian III coming in to Hanworth (Flight magazine 11 July 1930)

While the airplanes were away, the crowd of spectators at Hanworth were entertained by flying displays, aerobatics and parachute descents. Around 6pm, to the amazement of the crowd – and the delight of the press photographers it can be assumed – Winifred Brown, who had led for most of the stages, arrived first in her Avro Avian III. Winifred thus became the first woman to win the King’s Cup.

Winifred Brown was not from the typical elite group of ladies who flew from garden party to country house. The daughter of a Cheshire butcher, Winifred was an international hockey star and an adventurer, sailing her yacht single-handed from North Wales to Spitsbergen in Norway. She learned to fly near Manchester and was the first woman to join the Lancashire Aero Club in 1927.

Winifred Brown winning the King’s Cup (Flight magazine 11 July 1930)

“..a woman was bound to win the race sooner or later” Flight, July 11, 1930

Winifred Brown at Hanworth, preparing for the race (Flight magazine, 11 July 1930)

Commander Perrin leading Winifred Brown in at Hanworth (Flight magazine, 11 July 1930)

Today most people have heard of Amy Johnson and Amelia Earhart, but less well-known are the early British women aviators like Winifred Brown, Winifred Spooner or the Ladies Bailey and Heath. All these women flew at Hanworth when it was one of the many Air Parks around London. Amy Johnson did not fly from Hanworth but visited in 1936 to christen the Florence Nightingale, the first air ambulance – she is named as Mrs Jim Mollison in the picture caption despite being the most famous British woman aviator.

Mrs Mollison (Amy Johnson) christens the Monospar air ambulance (Flight Magazine, 11 June 1936)

Women were going up in airplanes not long after the Wright Brothers first flight in America in 1903. The British Hilda Hewlett was entranced by airplanes demonstrated in a rain-sodden field in Blackpool in 1909.

After learning to fly in France, she ran a flying school out of Brooklands, despite, as a woman, not being allowed to use the club house.

Hilda Hewlett called herself Grace Bird – her husband objected to her name being used in such a “silly escapade”

Bessie Coleman with her airplane 1922

What attracted women to flying? The same reasons as men: the challenge of a new and exciting sport – but many early aviators described the joy of leaving the ground and soaring to the heavens as an almost religious experience. For women in the early twentieth century, however, flying was also a way to escape the role of drudgery or society hostess, depending on your social status. It was a symbol of emancipation, along with the new-fashioned bobbed hair and short skirts. For Bessie Coleman, excluded from flying schools as a woman of colour, it was a way to escape her background of sharecropping.

Many flew simply for the fun of it: Dorothy Spicer and Pauline Gower wrote about their air exhibitions and air taxi service in Women with Wings which they said should have been called Two Girls in a Plane.

“Dorothy, the throttle’s bust. What shall we do?”

“ No it isn’t, you chump. I’ve only got a suitcase on it”.

Dorothy Spicer (left) and Pauline Gower (Women with Wings, Pauline Gower, 1938)

Dorothy Spicer (left) and Pauline Gower (Women with Wings, Pauline Gower, 1938)

In fact, both ‘girls’ held their A and B pilots licences and the harder Navigator’s licence. Pauline Gower went on to be the Women’s Commandant of the Air Transport Auxiliary during the Second World War.

Women pilots at the first All Ladies meeting in 1931, Northamptonshire (Flight Magazine 25 September 1931)

A ban on women pilots was introduced in Paris in 1925 but overturned within a year to herald a golden age of aviatrices who could enjoy movie star status due to the public fascination of conquering long-distance routes. The new wooden-framed machines like the De Havilland Cirrus Moth were so light that they could be moved around by their tail and folded their wings to be stored in a large garage.

Flight Magazine 24 July 1931

Some women aviators threw themselves into the glamour of flying; Hanworth marketed itself on the ‘well-equipped club’ with ball-rooms and lounges and wanted to create a Henley Regatta for the new sport of flying.

Other women were clear about their feminist aims. Sophie, Lady Heath, who held a degree in physiology and qualified as a mechanic in the US, courted publicity. Nicknamed ‘Lady Hell-of-a -Din’ by the press, she campaigned strenuously for the rights of women in sport, touring the country giving lectures. Other women wrote in the Girls’ Own Paper of their flying exploits to encourage girls to consider flying as a sport or even a career.

Lady Sophie Heath (Flight magazine)

Like Lady Heath, Lady Mary Bailey was Irish but was much more publicity-shy than her countrywoman. She was the first woman to fly across the Irish Sea and the first woman to fly solo to Cape Town at her second attempt in 1928. She was one of the 96 competitors in the King’s Cup at Hanworth in 1930. Together with Lady Heath, they set an altitude record in 1927.

Lady Mary Bailey (right) (Flight Magazine 14 July 1927)

Most famous of them all was Mary du Caurroy, Duchess of Bedford, known as the Flying Duchess. A true eccentric, she took up flying at the age of 60 having been told that it would help cure her tinnitus. At 67, she obtained her pilot’s licence and used her airplane to avoid ‘wasting time’ when visiting friends but also to fly long distances across continents. She called it ‘the most exhilarating of sports’ and pumped petrol and made time and distance calculations or navigated when not flying herself. The rest of the time she knitted – once at 13,000 feet, she found the air so cold that her fingers were too numb to knit. She hated the social scene which she was born to inhabit but would agree to give lectures to encourage women to take up flying. Although she did not take part in the King’s Cup in 1930, she agreed to open the event at Hanworth, which ensured that the race made the front pages.

The Duchess of Bedford opening Hanworth (known as the London Air Park) on 31 August 1929. (Flight Magazine 6 September 1929)

The only woman to earn her living as a pilot in the early years was Winifred Spooner. Renowned for her reliability and flying skills, she went solo after only 12 hours and passed her A licence after a further six hours. She was a capable mechanic on both airframes and engines; even the grumpy editor of The Aeroplane, C. G. Grey, admitted that ‘few, if any, men pilots, are better than she was’.

Sources and Acknowledgements

Online:

British History Online. Available at: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol3/pp114-119 Accessed 1 March 2018

Flight Magazine. Available at: https://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/. Accessed Feb – May 2018

Books and articles:

Aeroplane Monthly Feb 1983. Lettice Curtis (extract from The Forgotten Pilots. (1985)

Aeroplane Monthly Dec 1982. Gordon Riley

Air Transport Manual 1933 (map photo of airfields)

Aviation News 10 – 23 Feb 1983. Don Conway

Bell, J. (2009) Miss Winifred Spooner. Self-published

Biard, H.C. Wings. (Undated). London: Husrt & Blackett Ltd.

Bix, A. S. Beyond Amelia Earhart: Teaching about the History of Women Aviators. OAH Magazine of History, Vol. 24, No. 3, History of Technology (July 2010), pp. 39-4

Boase, W (1979). The Sky’s the Limit. London: Osprey

Brown, W. (1952) No distress signals

Buxton, M. (2008). The High-Flying Duchess. King’s Lynn: Woodperry Books

Chiltern Aviation Society (1979). From Airships to Concord: A History of Aviation in West London

Feltham Arts Association ((1997). Hanworth Air Park 1916 – 1949. Feltham Community Arts Association

Gower, P (1938) Women with Wings, published John Lang 1938. https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1500043448

Heath, S. and Murray, S (1929), Woman and Flying. London: John Long Limited

Hewlett, G. (2010) Old Bird: The Irrepressible Mrs Hewlett. Leicester: Matador

Map/Legend (photo) undated probably 1984, associated with lecture given by Ken Mason.

Marck, Bernard. Women Aviators: From Amelia Earhart to Sally Ride, Making History in Air and Space. Flammarion

Middlesex Chronicle, 28 Sept 1989 p19 (Vera Scott asking for help for Air Park 1916 book)

Sherwood, T. (1999). Coming in to Land. Middlesex: Heritage Publications

Vintage Aircraft [Magazine] no. 15 Jan – Mar 1980 – Memories of Air Racing in 1930s.

Wade, Valerie. (2012) Amy and the Aviatrices. Leeds: Zeteo Publishing

Yount, Lisa (1995), Women Aviators. New York: Facts On File

Permissions to publish images acknowledged with thanks:

HOUNSLOW LIBRARIES LOCAL COLLECTION, FELTHAM LIBRARY

Flight Magazine images courtesy FlightGlobal: part of RBI, reedbusiness.com

All text copyright The Environment Trust and credited to Laura Polglase as the Author